Sometime, over the next week, a powerful storm will rumble in on its westward path through the Great Plains. The wind gusting at record-setting speeds will blow pollen, dandelions and gray leaves over Washington and set the stage for the worst allergy season in decades. Many people will find themselves nursing reactions that seem odd, even distressing, but they have reason to cheer: Washington is one of the most tree-friendly cities in the United States.

In many regards, that’s a good thing. When trees shed their leaves, a sustainable means of capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) during the first weeks of the year and releasing it only when the leaves fall or are dried, the air is a more efficient, less carbon-intensive burner of the planet’s one-third of the total Earth’s CO2 emissions.

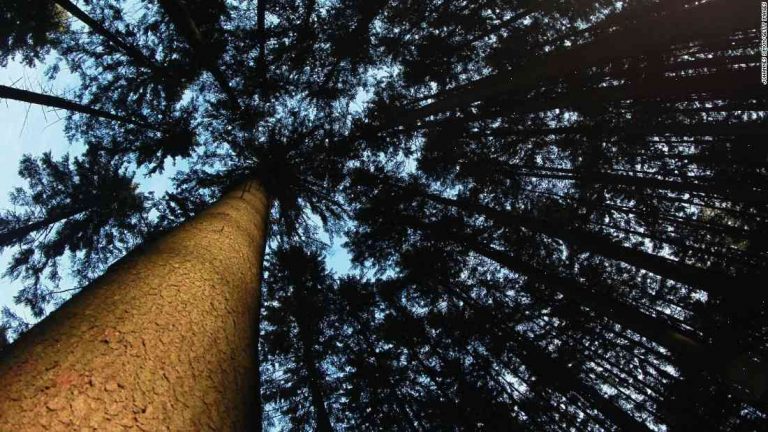

But that carbon capture, more in theory than practice, is why cities like Washington need as many trees as possible: It helps reduce CO2 emissions that cause global warming. And trees grow slowly. The planting of 1 million trees has the power to absorb 300 tons of CO2 from the air every year, in a region as diverse as the District. If all of Washington’s nearly 200,000 trees are perfectly healthy, it would result in the district releasing 27 million fewer tons of CO2 per year than if the trees had been planted at a rate of one tree for every 80 people. That’s an extra 32 tons of emissions per day over four decades, and 1.5 billion tons a year less in greenhouse gases.

Those are huge numbers, and they begin to move in the right direction when you consider that 40 percent of the planet’s CO2 emissions come from urban areas, and are predicted to continue rising for the foreseeable future. Yes, the construction of new houses and schools leads to some green releases. But when an average resident produces only one ton of CO2 per year, or 400 trees a year, it begins to look like climate change is unlikely to have an extraordinarily large impact.

You would be much better off planting a billion trees than building a new house and sticking a Dumpster in your backyard. At the moment, Washington has fewer than 3 million trees, though efforts to curb the city’s massive trash run-off and city-wide tree planting has lead to over 33,000 new trees in the past five years. Should the city lose its last 10,000 trees and try to rebuild its tree population, that would only mean a modest reduction in carbon emissions.

Thus, Washington is actually in a pretty good position to grow and renew its forests.

How can we make this happen? One idea is to institute a canopy canopy rating system, like those found in cities such as New York City and San Francisco. (Besides the shade and breathing benefits, cities that adopt canopy-rating systems get a boost from residents who begrudgingly to clean and plant their own trees and contribute more to the cost of the local public spaces.) Another possibility is to build “climate-friendly municipal parks,” as MIT science professor Nicholas Martin put it in an interview with Vox.

There is no shortage of funding possibilities for research and new tree planting efforts. Through National Geographic’s Green Capital Fund and the Brookings Institution’s Center for Cities, for example, research grants have been awarded to 22 cities nationwide, including Washington, for studying or planting trees. The best cities for a canopy rating system will have a more consistent program for expanding and maintaining their urban forests. In Washington, that remains one of the biggest problems; most neighborhoods outside the downtown region have little or no green canopy and few neighborhoods have real trees.

Tree campaigns across the country will also need coordination from city governments, as well as from conservation groups. Who collects and uses the data? Which city agencies get the priorities and allocation of funds? All of these issues will require continued government attention in the years to come. But this was an issue worth the effort.